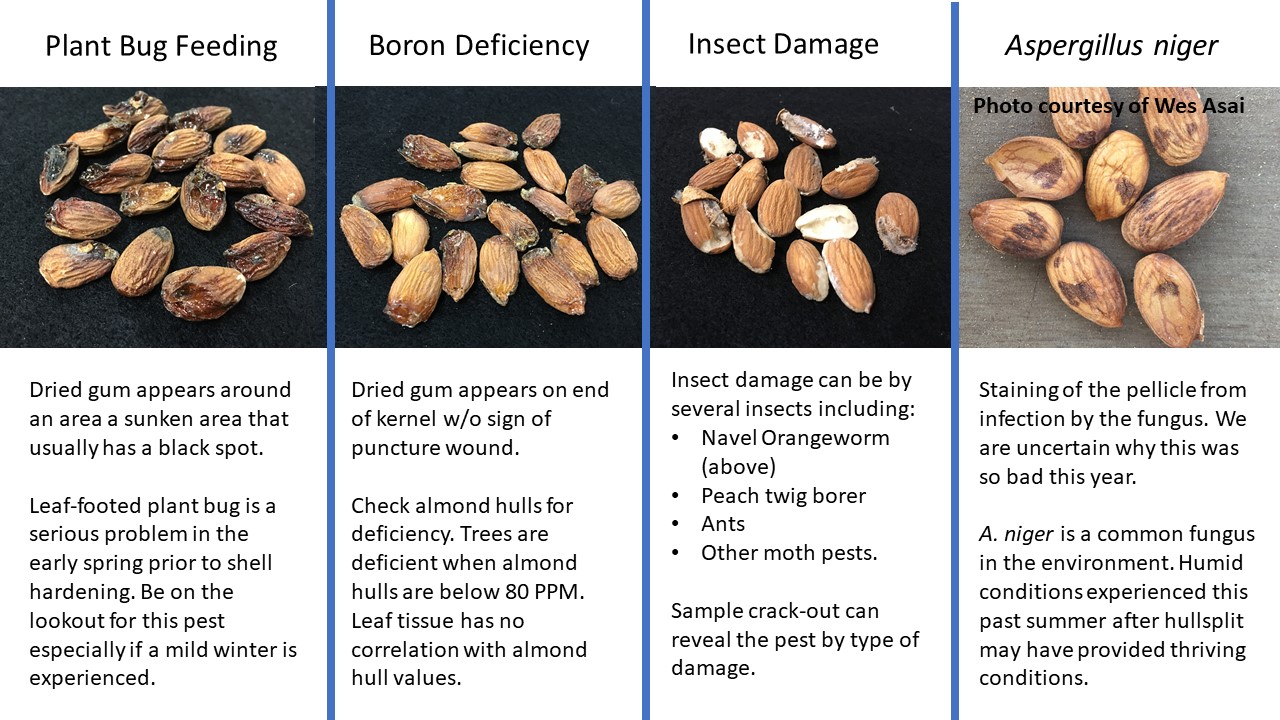

It has been a challenging year in regards to kernel quality within almonds. Several issues have emerged including insects, diseases, and deficiencies. Samples of each of these have been brought to the office for identification. In doing so, I thought it would a good idea to share what we have found with the accompanying figure.

Each of these problems seem to have a set of circumstances that led to an increased observance of the problem in 2017. They include:

- Leaf-footed plant bug. These large bugs damage the kernel by feeding. There was a larger over-wintering population in 2017 which is thought to be due to the milder winter and increased vegetation that occurred from the increased rain. Damage was reported on nearly all varieties, but was particularly bad on ‘Aldrich’ and ‘Fritz.’ If the feeding occurs early in the season it will kill the kernel. Later feeding occurring as the shell hardens and the embryo matures will not kill the nut but cause staining and sometimes gumming. The defining characteristic is a sunken black spot located on the kernel.

- Boron deficiency. This deficiency can occur in areas with clean surface water and low soil boron and is observed regularly on the east side of the central valley. Boron deficiency can lead to gum that crystallizes on the end of the kernel and is not in response to a feeding wound. A hull analysis should be conducted to determine boron levels as leaf levels are not indicative of tree boron status. A hull analysis under 80 ppm indicates deficiency and boron should be applied to the soil to bring the trees to sufficient levels.

- Insect damage. Navel orangeworm (NOW) was high this year with reports as high as 40% in late harvesting varieties. Lack of winter sanitation due to the rains and increased daily temperatures in July and August led to higher populations. NOW is easily identified by frass visible when opening kernels. Other insects can causes losses too. These include ants (which often eat everything but the pellicle) and peach twig borer (which usually doesn’t tunnel into the kernel). A crack-out sample should be collected after shaking but prior to sweeping in order to identify the insect pest causing the damage.

- This year we observed an increase in pellicle staining from Aspergillus niger. This fungus is common within the environment and is an opportunistic pathogen. Although we don’t understand everything regarding the widespread occurrence, it is speculated that the high humidity experienced after hull-split provided the climate conditions conducive for infection. Although common on ‘Nonpareil’ this year, we have seen this on ‘Sonora’ and other varieties in the past.

Taking samples from the field during the harvesting process provides feedback on the pest management practices applied and should be done. If relying on the processor for a damage report, it is most likely that the damage is much higher in the field. This is especially true with insect damage as much of the damage is lost during the harvesting process and diluted due to processors indicating damage by weight, not count. We have found that damage can be nearly twice as high in the field in comparison to the processing report.

Kashmir Csaky

May 5, 2019I have seen black staining on the shells of almonds. Is this also Aspergillus niger? I feed almonds to my birds in shell and the staining has me concerned.

David Doll

May 26, 2019My guess is that it is either A. niger or Rhizopus. Either way, neither of these fungi are non-toxigenic and have no effect if consumed.

David

David DENIZ

May 31, 2019My crack out on my butte padre in 2018 was only 20% I have never had that low of crack out % has any one with butte padre complained about low crack out numbers on 2018 crop.

David Doll

June 23, 2019Dear David,

How was your crop load? Irrigation practices during the summer? A high nut count will often lead to smaller kernels. Stressing the trees through the summer can lead to reduced energy for nut development, leading to smaller kernel sizes. Maintaining reduced stress levels will help maximize kernel size.

David