Katherine Pope, UCCE Farm Advisor Sacramento, Solano and Yolo Counties

Part 1 of 3 in the series – What can we learn from the low chill winter of 2013-2014

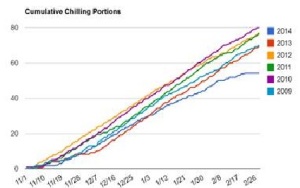

With harvest wrapped up, it’s a good time to take stock of the impacts of the warm winter of 2013-2014. Average chill was down 25% in the Central Valley, falling behind in January and never catching up. Orchards in many crops showed classic symptoms of low chill – delayed and extended bloom, poor pollinizer overlap and weak leaf-out. Prolonged bloom likely resulted in some cherries, pistachios and prunes experiencing warmer bloom temperatures, which decreased yields for many. Drought-related water stress likely contributed to some of the yield, size and quality issues we saw at harvest. But low chill was almost certainly responsible for a great deal of the unusual tree behavior, low yields and poor quality. So what can we learn from this tough year moving forward?

First, do we need to bother to learn from last winter? Was it just a blip on the radar? Or is last year’s winter the new normal? The answer lies somewhere in between. We should not expect winters like this every year, but we should expect them to come more frequently.

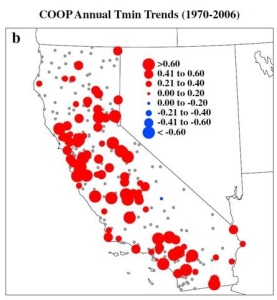

An occasional low chill winter is nothing new for California. Agricultural records since the 1950’s show we get low chill every 10-20 years. It’s likely that these cycles will continue. But overall temperatures are getting warmer in the Central Valley. Weather records show annual minimum temperatures have gone up more than 4° F in the Central Valley since 1970 (Cordero et al. 2011). This might not seem like a lot, but it’s enough to change a warm winter from “just enough” chill to “not quite enough.” As temperatures continue to warm, which the vast majority of climate scientists calculate they will, we can expect winters like 2013-2014 to come about every 10 years (Luedeling et al. 2009).

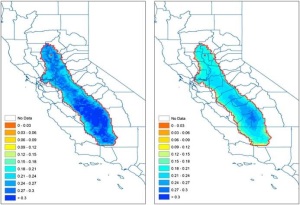

On top of this, we know fog is decreasing in the Central Valley. I remember many white knuckle mornings driving to school on the Delta river roads. Mornings like that don’t come like they used to. Days with significant fog have decreased from 3 out of every 10 days in the 1980’s and 1990’s, to a little less than 2 out of every 10 days in the last decade (Baldocchi & Waller 2014). That one day means a 33% reduction in fog. This is important for tree crops and chilling because the fog can essentially shade flower buds from the sun. With reduced fog, buds are likely feeling even less chill than air temperature changes are telling us. There are no chill models that include the impact of fog right now, so we don’t know just how much difference this is making.

Put together, winter chill has been decreasing and the winter chill that the buds are feeling is likely decreasing a bit more because of less fog. Luckily for California’s tree crop industry, there are many potential solutions to decreased chill in the Central Valley. Some of these solutions are available now. Some need more research, testing and approval before they can be put into use in the field.

The first step to preparing for more warm winters is counting chill better. According to the chill hours model, last winter was actually an average chill winter. The trees obviously did not agree. In the next post, I’ll explain how to use another model, the Dynamic Model, which seems to count chill more like the tree buds. The better we count chill, then better we’ll know when we need to act. In the post after that, I’ll discuss in-orchard low chill management, particularly how dormancy oil in has been shown to be useful in pistachio in low chill winters.

Note: I realize talking about increasing temperatures may raise some hackles. I am not a climate scientist, I am a plant scientist. Never-the-less, 97% of climate scientists believe temperatures are increasing, and will continue to increase. If I see 100 doctors and 97 of them tell me my cholesterol is too high, I’m going to believe them and make some changes. Regardless of the cause of the increase, this will impact how we farm in California. There is plenty that we can do in California agriculture to prepare for warmer winters. The sooner we start talking about those solutions, and supporting those solutions, the more prepared we can be.

Patrick Dosier

November 9, 2014Great article Katherine, thank you for posting.

Is there reason for growers to consider collecting unshielded air-temperature measurements? Or can we work data from a pyranometer into the model?

Either way, I am advising my clients to reference the Dynamic Model going forward…

–Patrick

Katherine Pope

November 21, 2014Glad you found the post informative, Patrick. I think shielded air temperature measurements are still the way to go for now. We don’t know how an unshielded sensor would respond to exposure when compared with an exposed pistachio bud. And the comparison would be different again when looking at the buds of a different crop. Until we know more about that level of complication, I’d stick with shielded sensors.

Navdeep Bains

November 11, 2014Great insight – definitely food for thought!

Counting Chill Better – Using the Chill Portions Model - The Almond Doctor

January 13, 2015[…] my last post, Is Last Year’s Warm Winter the New Normal?, I discussed low chill winters like last year’s coming more often in the near future. The first […]